Maize Markets in Kenya and Malawi Show Dysfunction, Experts Call for Regional Interventions

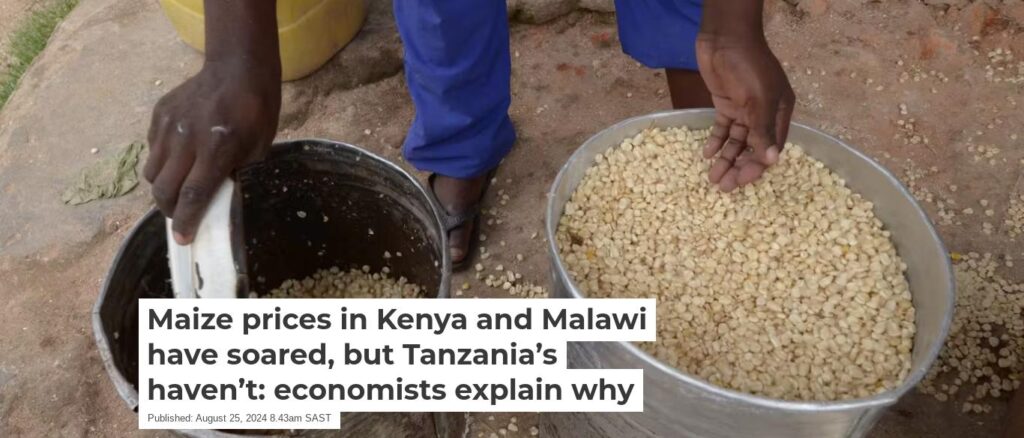

Maize, the leading staple food in East and Southern Africa, has seen a stark contrast in pricing trends across the region. While countries like Kenya and Malawi are grappling with soaring maize prices, Tanzania has managed to maintain relatively stable prices.

Economists from the Centre for Competition, Regulation, and Economic Development at the University of Johannesburg, Namhla Landani and Arthur Khomotso Mahuma, have analyzed the factors contributing to these disparities, calling for regional cooperation to address market dysfunctions.

For more than a year, maize prices in Kenya and Malawi have been significantly higher compared to other countries in the East and Southern Africa (ESA) region. In Malawi, high fertilizer costs, exacerbated by global supply shocks in 2022, led to reduced fertilizer usage and subsequently lower maize production.

This issue was further compounded by adverse weather conditions and trade bans, resulting in a poor harvest in 2023. Despite these challenges, Malawi’s maize prices remain excessively high, with a 63% markup over the import parity price, which is the cost at which maize could be imported from surplus-producing countries like Tanzania.

Kenya, on the other hand, has experienced high maize prices driven by excessive profit margins. Sellers in Kenya have been charging prices that far exceed the import parity price, adding to the burden of the 1.2 million people in the country facing acute food insecurity. From January 2023 to April 2024,

Kenya’s maize prices were marked up by an average of 82% above the cost of importing maize from Tanzania. Although prices dropped sharply in May 2024 due to increased imports and the release of hoarded maize, they still remain 50% above the import parity price.

In contrast, Tanzania has enjoyed bumper maize harvests in 2023 and 2024 due to favorable weather conditions. The country has emerged as a key supplier of non-genetically modified maize to the region, with an estimated 4 million tonnes of excess maize available for export. This surplus is seven times the projected import requirements for Malawi in 2024 and sufficient to cover the region’s overall maize deficit.

Despite Tanzania’s abundance, the dysfunctional maize markets in Kenya and Malawi have prevented these countries from benefiting from the lower prices that should result from regional trade. If the markets were functioning properly, maize prices in Malawi and Kenya would reflect the prevailing prices in Tanzania, plus associated import costs.

Landani and Mahuma emphasize that the dysfunction in maize markets in Kenya and Malawi highlights the need for a regional approach to market monitoring and regulation. Competition authorities must take action to assess and remove barriers to regional trade and intervene in cases of anti-competitive behavior. By ensuring that regional markets operate efficiently, authorities can help stabilize maize prices and improve food security across the region.

The economists also stress the importance of addressing the underlying factors contributing to market dysfunctions, such as high input costs and trade restrictions. In Malawi, for example, the government’s Affordable Input Programme, which provides subsidized fertilizer to millions of households, needs to be more effectively managed to ensure timely procurement and distribution.

The current state of maize markets in Kenya and Malawi is unsustainable, with prices far exceeding what would be expected in a well-functioning regional market.

The situation calls for urgent intervention from competition authorities and regional bodies to ensure that the benefits of surplus production in countries like Tanzania are shared across the region. Only through coordinated regional efforts can the ESA region achieve food security and price stability for its most essential staple food.